Any Open Source, Any Ecosystem

Supported open source ecosystems

ActiveState regularly imports open source packages, libraries, frameworks, and applications from popular ecosystems, verifies their security and integrity, and then makes them available to you via our immutable catalog. As a result, you can manage a single, trusted point of open source ingestion rather than multiple upstream sources, vastly simplifying the effort to secure your software supply chain.

Whether you’re a coder, IT manager, security professional, or a compliance expert, ActiveState lets you create a curated catalog of secure open source assets that adhere to your internal guidelines, industry rules, and government regulations without having to worry that they may no longer be available from the community years from now when you need to rebuild your app.

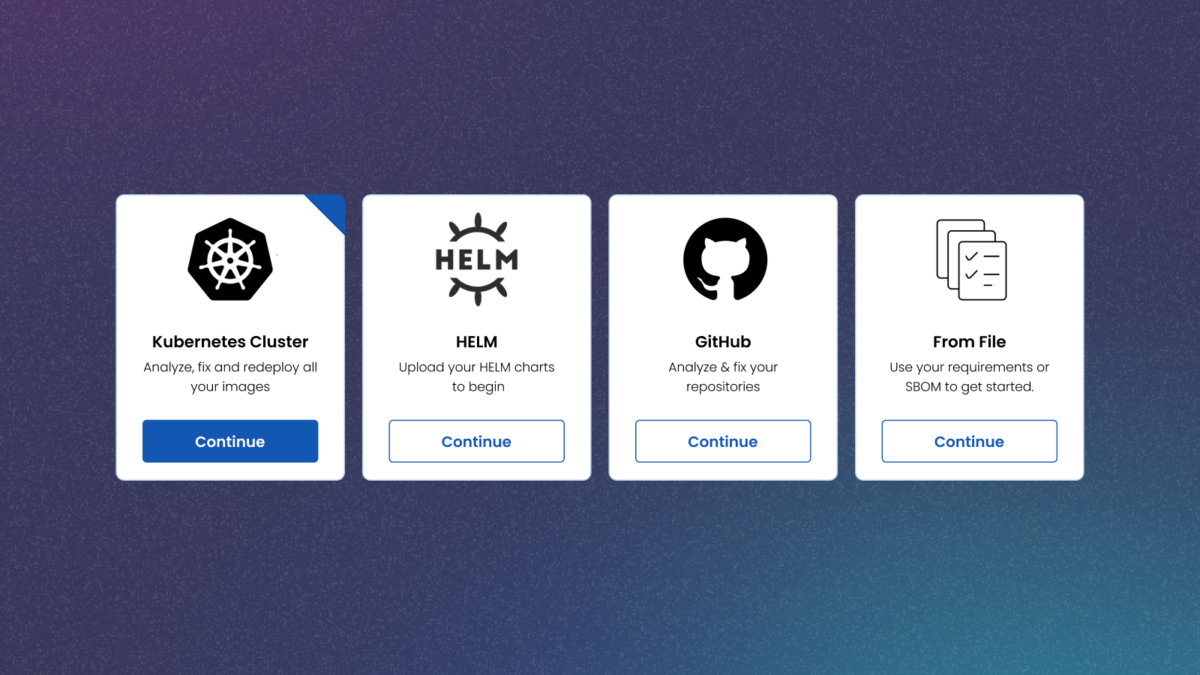

Universal discovery

ActiveState discovers and catalogs all the open source applications, packages, libraries, and frameworks in use across your extended enterprise, no matter the ecosystem or deployment environment.

The result is a central source of truth that eliminates the security and compliance risks associated with phantom (i.e., undiscovered) dependencies other solutions miss.

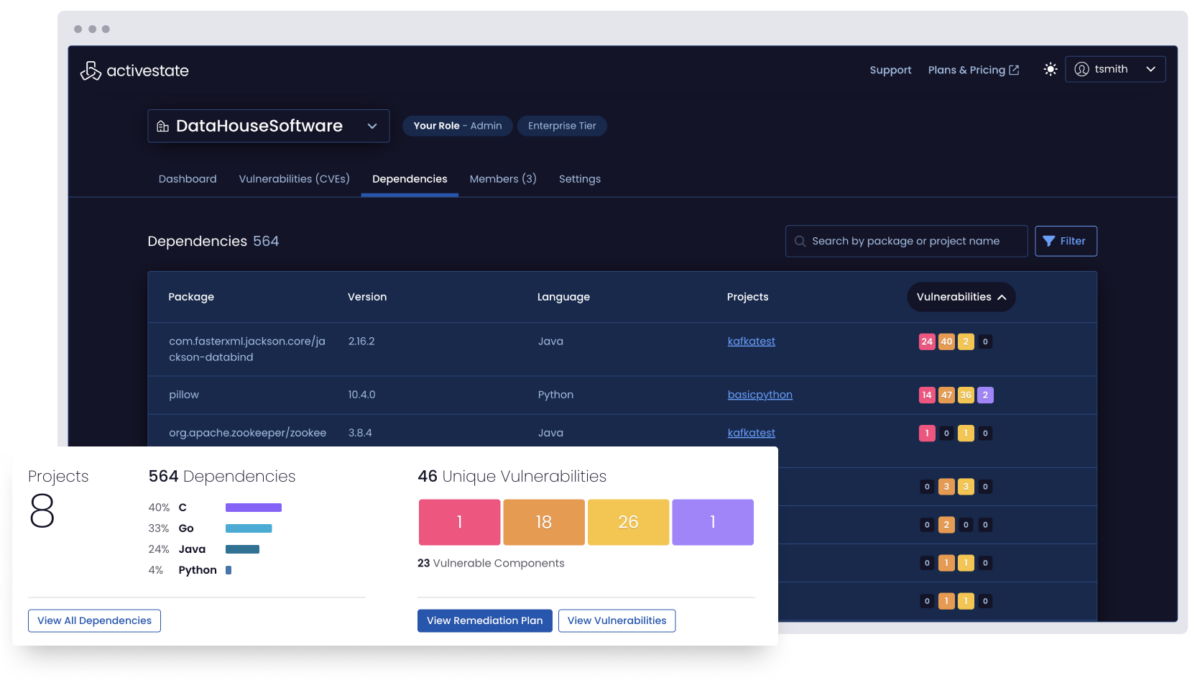

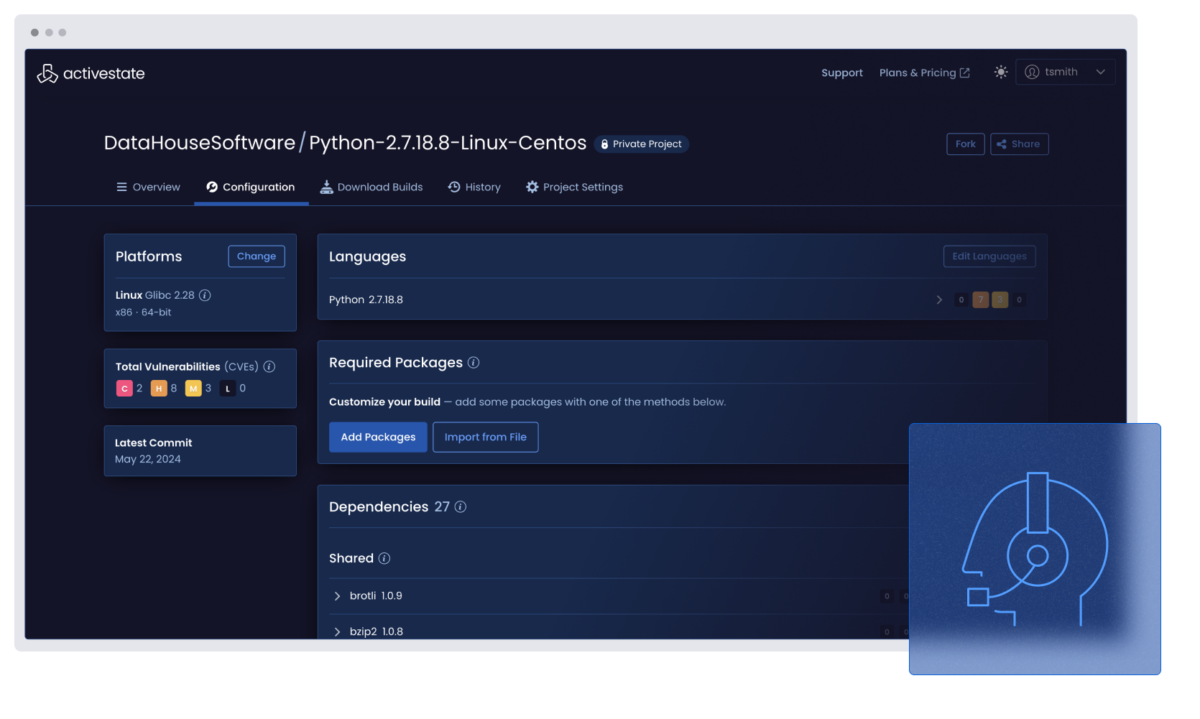

Universal observability

ActiveState uncovers the vulnerability status for all open source dependencies, tracks changes over time, and notifies appropriate stakeholders when vulnerabilities occur, decreasing Mean Time To Detection (MTTD).

And when changes occur, ActiveState tracks who made it, in which project, and when it happened, creating an audit trail you can use for forensic analysis to discover root cause and eliminate errors going forward.

Redistribution

ActiveState regularly pulls packages from numerous public repositories and makes them available as curated distributions in order to simplify installation and usage for you.

ActiveState language distributions are 100% compatible with open source distributions but come with additional tools, centralized configuration management, git-like snapshots, reporting and auditing, and a wealth of other benefits that can help make your teams more efficient and productive.

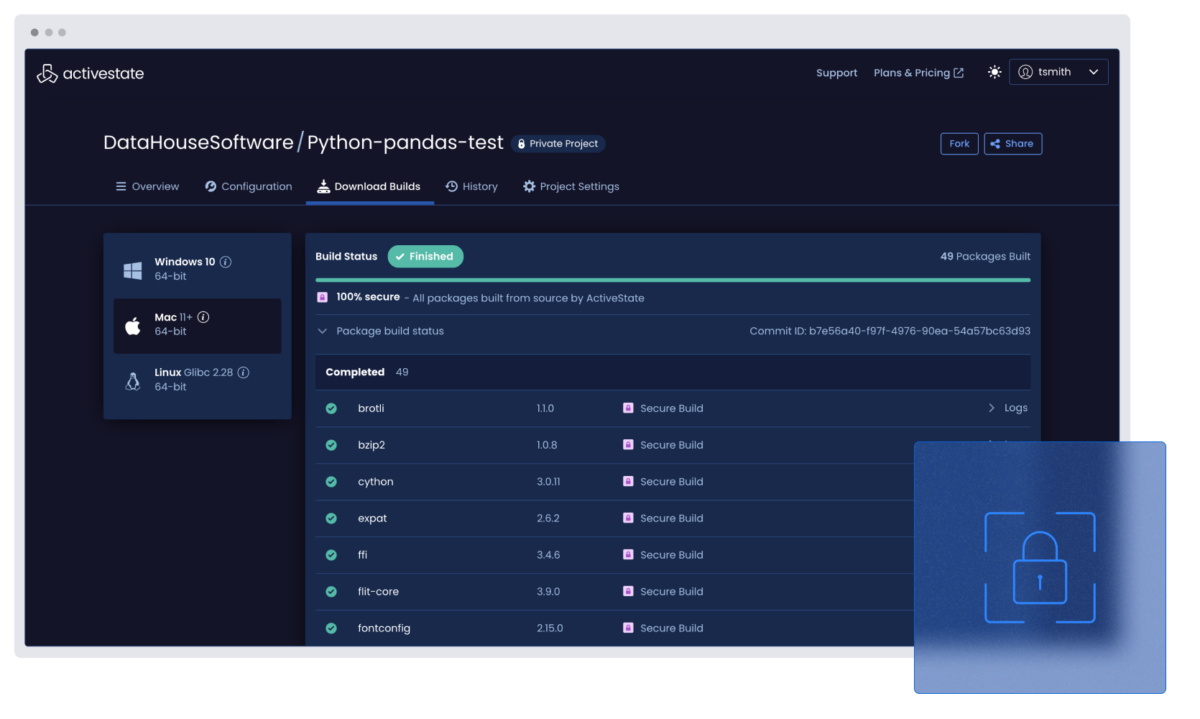

Automated builds from source

ActiveState provides the ability to automatically build runtime environments from vetted source code using our secure build service based on the Supply chain Levels for Secure Artifacts (SLSA) standard’s Build Level 3.

The only way to ensure open source security is to build it reproducibly from source, but it’s always been too resource and time intensive to do at scale. With the ActiveState platform, you can finally scale up your open source usage securely.

Beyond EOL support

ActiveState provides extended support for a number of open source ecosystems, ensuring your enterprise can continue to run older applications securely.

Let ActiveState backport security fixes for your application’s language core, as well as its standard libraries and third-party packages so you can shift your scarce developer resources from creating patches to driving innovation.

One platform. Multiple languages. Fully managed.

ActiveState Python

Secure your entire Python ecosystem, not just ActiveState Python. The ActiveState platform helps you automate builds, manage dependencies, and maintain compliance across teams and environments.

ActiveState Go

From microservices to enterprise systems, Go projects thrive with consistency. ActiveState gives you a secure way to build, share, and govern all your Go environments across teams, pipelines, and deployments.

ActiveState Java

Bring control and clarity to all your Java, not just ActiveState Java. ActiveState lets you manage builds, dependencies, and compliance from within a single view, making it easier to keep your Java projects secure and aligned across your enterprise.

ActiveState R

R environments can be difficult to standardize regardless of where you are in the product lifecycle. ActiveState helps you build reproducible, secure R environments that meet compliance requirements and scale with your team.

ActiveState Perl

Managing Perl shouldn’t be a black box. ActiveState helps you modernize and maintain all your Perl applications with a secure, centralized approach that improves collaboration, versioning, and policy enforcement.

ActiveState Tcl

Tcl is powerful, but managing dependencies and environments at scale can get messy. ActiveState brings visibility and control to all your Tcl usage, ensuring builds are secure, compliant, and consistent across systems.

ActiveState Ruby

Simplify how you manage Ruby across your organization. ActiveState provides secure Ruby builds, streamlined dependency management, and compliance tooling so teams can focus on shipping code, not maintaining environments.

The ActiveState platform manages 40 million unique artifacts across multiple language ecosystems.

Get in touch to discover more supported languages.